Frank Gage recalls life as a child in a railroad camp once used in logging operations in the Pacific Northwest.

HOQUIAM, Washington—It’s not uncommon to meet Rayonier employees who have been with the company for more than 30 or even 40 years. But 64-year-old Frank Gage holds the record: a lifetime at Rayonier.

In fact, one could argue he was born into the company. His father was a Rayonier safety manager, so their family lived on Rayonier land. Their house was at the old Polson Railroad Camp near Hoquiam, allowing Frank’s dad to quickly hear about—and respond to—emergencies.

When Frank was born, he came home to the camp. His earliest memories are made up of adventures in the woods: trying to play with bear cubs, going berry-picking in the woods, and watching the excitement of the loggers and railroad at work.

Frank remembers Rayonier once hired a bounty hunter who was paid to capture animals that were a nuisance to the logging crews.

“The guy came into camp one night with a cougar strapped to the roof of his car,” Frank says. “It was as long as the car, from the hood to the tailgate!”

Frank was there when Rayonier held a special ceremony to celebrate the transition from steam engines to diesel trains. In fact, he was captured on camera: he was standing next to his brother and another boy, who were eating ice cream at the celebration.

The Backstory on Railroad and Logging Camps

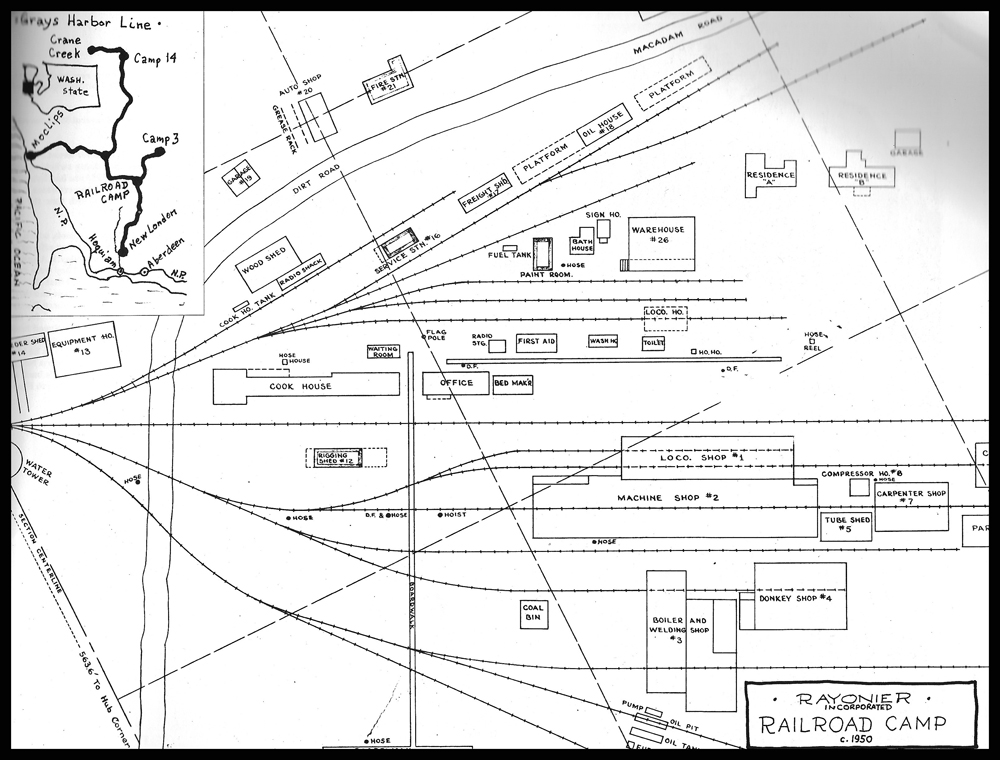

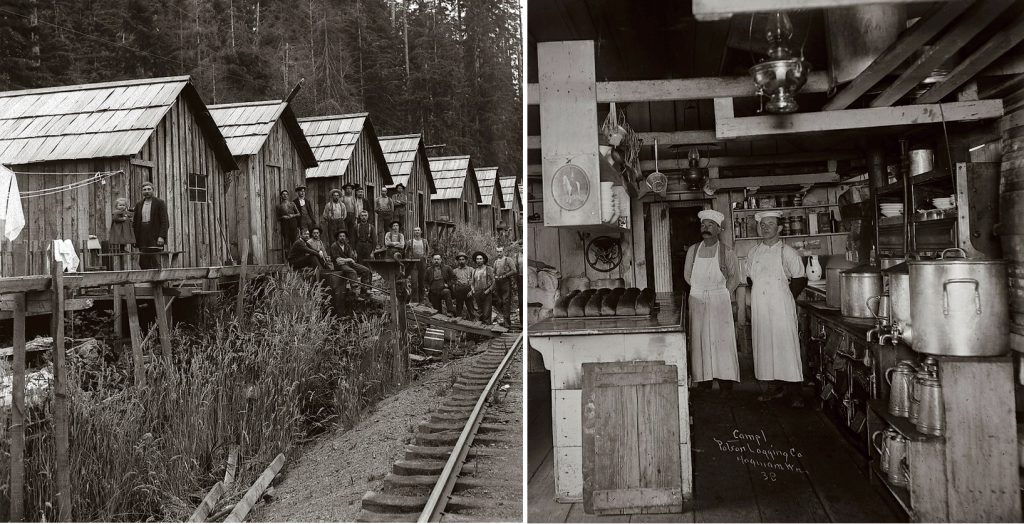

When Frank’s family lived at the camp from 1956-63, there were about a dozen homes and a few shops for maintenance and repairs. That was nothing compared to the bustling scene that once was the Polson’s railroad and logging camps.

Rayonier purchased Polson Brothers, a logging company, in the 1940s. It came with land, camps and its own railroad line. In the decades prior to our purchase, the camps were home to dozens of loggers and railroad employees. They packed up their belongings and lived there for months at a time.

Logging Camps provided workers the basics deep in the woods

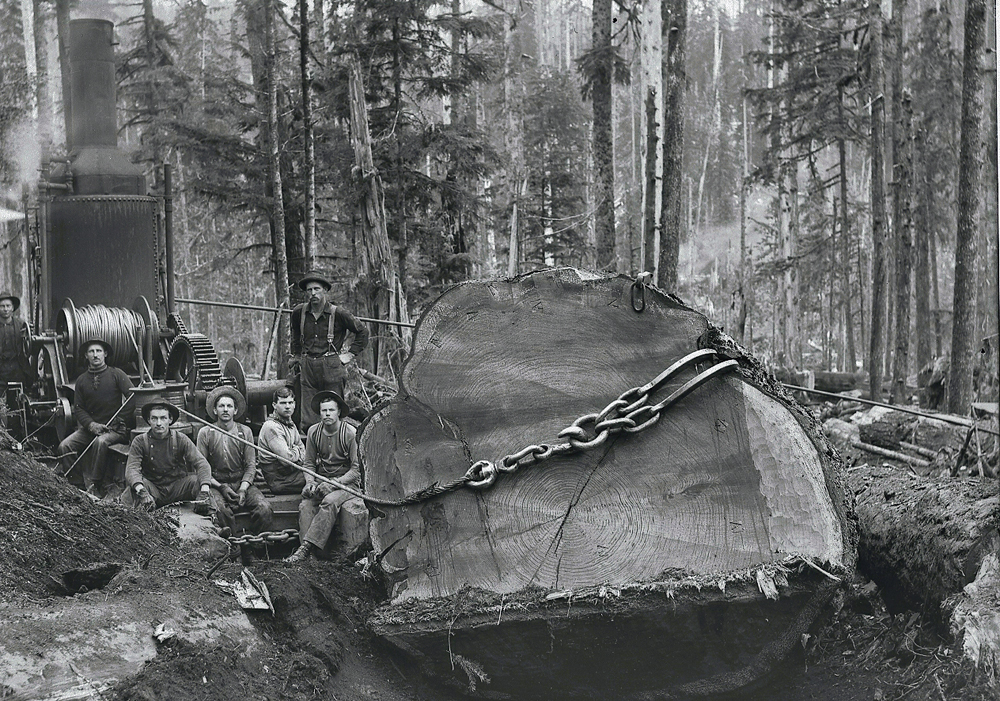

The loggers woke up early, heading into the woods after a quick coffee before sunrise. The loggers’ camps were along temporary railroad spurs they had built to access their logging sites. They used horse power and what was called a “steam donkey” engine to move equipment and timber. The engine used a cable system to pull itself on a “sled” typically made of logs. It also used cables to move heavy loads.

Loggers would load railroad cars with as many logs as they could safely hold, then a small locomotive would pull the cars to the main line. There, they would join with other cars and a powerful steam engine that would carry them out of the woods. Here in Hoquiam, the railroad led to the Hoquiam River, where loads were dumped into the water and guided downstream to the Hoquiam mill.

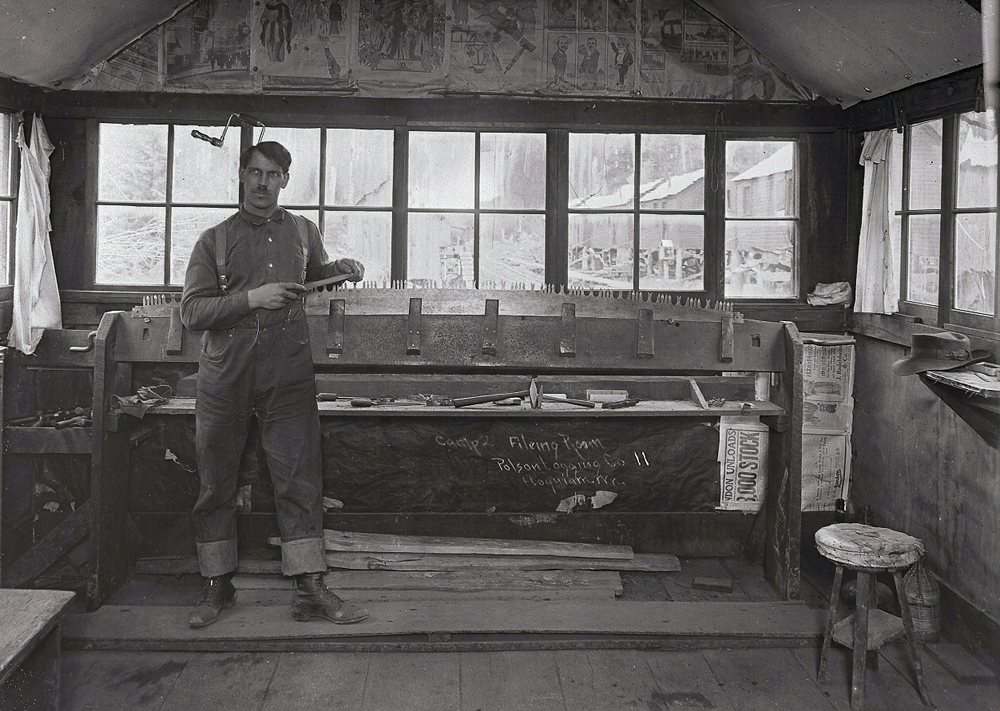

After a hard day’s work, the loggers would head back to camp for a hearty supper made by the camp cooks. There was also a repair shop for any broken saws and equipment. The loggers lived in small bunk houses on wheels that could be moved on the railroad line.

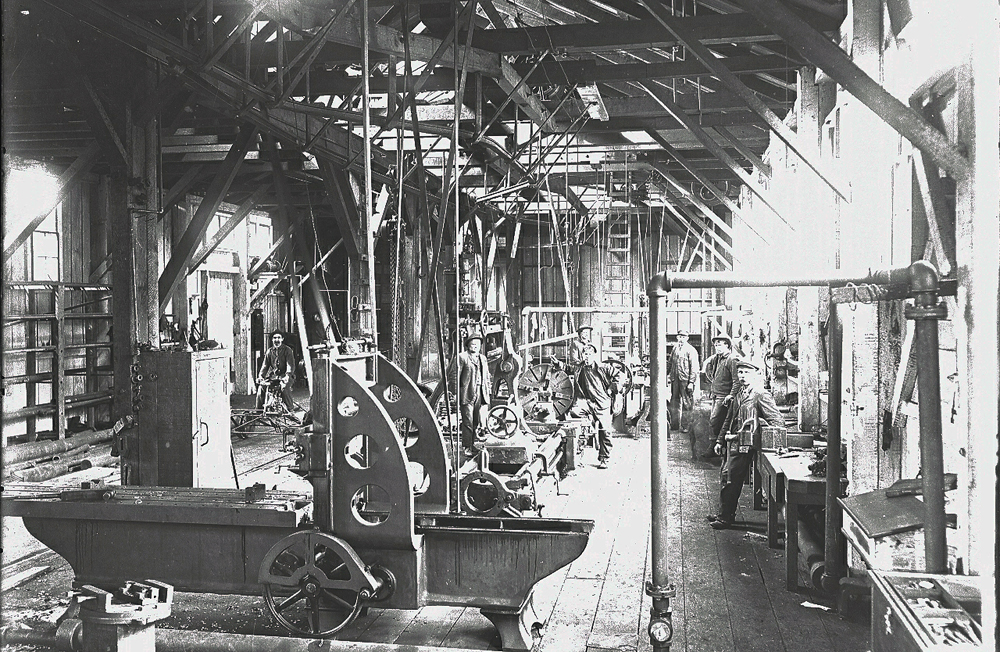

Railroad Camp was a central place for repairs

The Railroad Camp, meanwhile, was like a busy little town in its heyday. This is where locomotives and cars were taken for repairs in large repair shops. Railroad workers, mechanics, and section crews lived at the camp.

That was in the early 1900s. By Frank’s time, some of the old bunk houses were taken off their wheels and cobbled together to build homes for Rayonier employees. His house was made from three old bunk houses.

Carving out his own logging career

Frank’s dad eventually took another job and left the Rayonier camp, but Frank never forgot the company. When he graduated school, there was no doubt he wanted to return to logging.

He started out on a Rayonier railroad maintenance crew. Known as “gandy dancers” or “section crews,” these teams had to repair sections of track that wore down over time. They traveled on the rails in a small, gas-powered vehicle called a speeder.

“Working on the railroad crew was the most fun I ever had,” Frank recalls with his signature chuckle. “We had a self-imposed quota to change out 30 ties a day. I remember I made $5.18 an hour. I used that money to buy a brand new Camaro!”

Frank next moved on to a “banding” job. His job was to place bands around the logs on the rail cars before they were dumped into the river. Today, stray logs can still be seen floating down the Hoquiam River. Logs are now transported more efficiently by log trucks, but in the early 1900s and up through the beginning of Frank’s career, the river was at times filled from end to end with log “rafts.”

In 1978, Frank began preparing logs for transport to the mills. After the trees were cut and moved to a “yarding area” to be processed, he used chainsaws to further cut and “clean up” large logs. Back then, Frank recalls, the trees were grown to a much larger circumference than they are today.

“Wood was 2-, 4- or even 6-feet in diameter back then,” Frank says. “I loved using my old chainsaw. It could cut a 26-foot log into a 13-foot log like it was slicing into butter.”

After 10 years working “union time” for Rayonier, Frank spent 18 years working as a contractor. Rayonier works with many small, local logging contractors all over the country, who support harvest operations, planting operations, road and bridge repairs, and more. Frank operated a skidder and worked in a “rig up crew,” which filled in on odd logging jobs.

Then finally, in March 2004, Frank became a salaried Rayonier employee. He is now a timber production forester, which means he oversees logging operations on specific tracts in Washington.

Logging on Familiar Ground

As fate would have it, Frank would be the forester in charge of logging the land where his childhood home once stood.

The camp closed in 1968, about five years after his family moved out. The houses were removed and a new generation of trees was planted on the property.

“It was pretty neat to log in my first backyard,” Frank says. “The logger used my old driveway as a log yard.”

A log yard is a flat, well-located area where logs are taken to be processed and loaded onto log trucks.

“Rayonier is a Home for Me”

For Frank, Rayonier has always been family.

It started with his grandfather, who worked at a Rayonier pulp mill. Then it was his dad, who was focused on safety. The same could be said for Frank. He emphasizes safety for himself, his coworkers and the crews he works with. On his hard hat, he has a large “Don’t Stay Near, Get in the Clear” sticker, reminding loggers to stand clear of logs while they’re being cut, moved and loaded on a logging site.

Now his coworkers are like a second family, and Frank appreciates the team he gets to work with every day. He also appreciates Rayonier’s ability to hold firm in both the good times and the lean times, noting the company always seems to “find the better markets” for its logs.

“In one way, shape or form, Rayonier has always been a home for me,” Frank says. “I was born into a Rayonier family, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Want to learn even more railroad history? Check out the Polson Museum in Hoquiam or visit their website at polsonmuseum.org.

Join the Conversation

Wow – what a great story Frank. Brings those pictures to life that you were part of those days! Congrats on a long career w/ Rayonier.

Really enjoyed the story!

Frank cool story, well done !!!!! Ric Graham ” GRAMBO “

Neat story! Enjoyed learning about the railroad camps and Franks’ life with Rayonier. Thank you for sharing.

No mention of Vince and the time he spent working on the train line up north ? Very interesting Frank , I recall the grade school crossing guards getting treted to a lunch trip up to the logging camp. Allan.

My 1st job was at Camp 14 in 1964 till the Army got me. From 1973 on till closure I was in Rayonier’s cutting crew. I have many, many, perhaps hundreds, photos that either I or the scalers took of falling the huge timber then. In the old photos you hardly ever see such sights as the wildly leaning, candelabra top cedars, some with very large trees growing on the sides of the cedar trees, sometimes 5 or 6. Very challenging and dangerous. I’d like to preserve these photos, maybe with the UW or WSU. I remember Frank and his brother quite well. Rayonier was a very good company to work for.

Jim, sounds like you had quite an experience working with the Rayonier team! The types of trees harvested and safety measures have changed a lot since then, but loggers are still some of the hardest working people you could ever meet. Sounds like you have a treasure trove of old photos. If you don’t mind, you might soon hear from our Rayonier historian, who is always looking to preserve our history and gather stories from years gone by.

Thank you, I shall respond immediately and hope we can save some of this history, I’ll write up everything as best i can of often astonishing sights I’ve seen in old growth cedar at Rayonier, the methods dealing with them, and their significance which will otherwise be lost forever. There aren’t many of us old growth loggers left, and Rayonier had some of the best.

My Dad was Gene Smith Jr. who worked as cat skinner for

Rayonier. We lived on Polson Rd till 1968

We will have to tell Frank — he remembers everything and everyone!